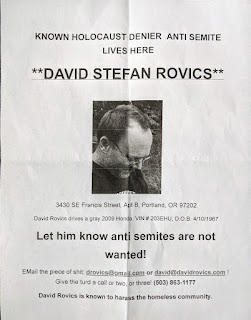

I'm doing a west coast tour next week, and the wackos are back, trying to intimidate gig organizers into canceling my little acoustic gigs, calling up farmers and people hosting house concerts to tell them I'm a Nazi. Welcome to my life in 2022.

I write a lot about politics, capitalism, social media, and the music industry. Sometimes about how all of these things intersect. Today will be no different, except with an emphasis on mental health.

I write about these things because I think about them so much, and I do that because they dominate my life. It's a good life, but there's a lot of room for improvement.

Broadly, over the past few days and weeks, aside from the usual backdrop of massacres, floods, fires, and famine, Ticketmaster has been in the news. The company is a massively profitable monopoly, making billions while so many other elements of the industry they largely run wither and die. And then they can't even operate a website well enough to manage a Taylor Swift concert tour so that her fans can buy the wildly expensive tickets they're selling, with their profit-maximizing algorithm, that basically allows them to charge as much as they can get away with.

Along with complaints about Ticketmaster, the music industry is in the news lately because of so many bands cancelling tours. Looking into it, the reasons for this that keep coming up revolve around the crazy economics of touring under the circumstances of an ongoing pandemic with wildly rising prices for everything involved with traveling, and mental health. These factors can't easily be separated from each other. I don't know if anyone has tried to figure out who is canceling tours solely for mental health reasons, and is unaffected by the economics involved.

Around three decades ago I was hosting open mics in the Boston area every week. There was an older guy, a poet, who was a regular. He was really good, and he often talked about the mental health of artists, and how sad it was that so many poets were depressed or suicidal. This was right around the time that Kurt Cobain killed himself, so there was plenty of broader context for his concerns.

There was a study from shortly before pandemic times that found that musicians are three times as likely as normal to suffer from depression or anxiety. The study explored various reasons for this. One particularly interesting observation is that this situation exists across the board for musicians, from those eking out a living playing in local bars to those packing stadiums.

There are big differences in the lives of musicians, some of whom are very rich and some of whom are very poor, to take one example of those big differences. But the similarities appear to be more powerful than the differences, at least as far as inducing depression and anxiety goes. Whether you're hopping freight trains or traveling in a tour bus, touring can be very isolating.

A typical experience with the touring life for musicians at all levels involves relatively short bursts of intense activity and social connection, such as a gig, followed by long stretches of relative isolation, such as being far away from most of your friends or family in someone's guest room or in a hotel room or some other unfamiliar location, or back in an overly-familiar location such as a tour bus or a red-eye flight.

There is a thrill, with lots of measurable chemical components, to performing, followed by what might often be comparatively like sensory deprivation, being alone in a car or van. The basic principle applies, whether you're playing for a crowd of fifty or fifty thousand.

There are many other common factors, such as the precarity of the profession. If you're used to packing living rooms for house concert tours, you wonder whether next year you'll get all those volunteer hosts wanting to book you again, and whether enough of those octogenarian folkies will be alive to attend next year's shows. If you just wrapped up a stadium tour, you're wondering whether you'll have a top 10 hit next year, to warrant the management company's interest in organizing another one.

At all levels, the experience of being on stage is addictive. At all levels, loneliness is lonely. At all levels, there is a profound uncertainty about what next year might hold for you and your profession.

Is it worse than it used to be? The study seems to be one-of-a-kind, so I don't know what data we'd try to compare it with, from the twentieth century, for example. The music industry has dramatically shrunk and become much more economically precarious over the past 25 years, so I would surmise that things have gotten harder for a lot of folks, across the board.

Another reason things have become more stressful across the board, I have no doubt at all, is due to the impact of what they call social media.

Even in the early days of Facebook, studies were finding that the more time someone spent on the platform, the more depressed they tended to become, even if what you were doing was generally just looking at the nice pictures your friends were posting. Add the more obviously negative and extremely common behaviors of so many people on social media, like insults, bullying, or harassment, and it's altogether much worse.

Before the internet, and especially before social media, if people wanted to say something about an artist, they could talk to their friends, or perhaps they could write an article in a newspaper. If they wanted to communicate with an artist, they could write a letter to them care of their record label, and hope they actually saw the thing. Aside from publishing an article somewhere, hosting a radio show, or talking to a room full of your friends, there was little opportunity for grandstanding or virtue-signaling, in comparison with the age of social media posting. If someone had something to say that was intended for an artist to hear, they could write to the artist directly. If they wanted to make a public statement, there were options, but they generally involved an editor or producer's input.

I don't know the percentages, but I think it's fair to say that a lot more artists than you might think read their fan mail, and even responded to it, in the days of print media and physical mail. In the age of social media, I'm quite certain this has not changed. This probably comes as no surprise when we're talking about the folkies on the house concert tours. But from my own, admittedly limited personal experience with knowing people who have hundreds of thousands of followers on Twitter, the rock stars (as well as the media stars, and members of parliaments around the world) get up in the morning and check their email and the notifications on their phones, just like the rest of us do. They may have staff helping them filter some of the incoming, but the basic phenomenon is the same, along with the associated emotional burden.

I had been thinking about writing something on this subject when I read about all those bands cancelling their tours on the grounds of mental health maintenance. But over the past couple days, I've been reminded that although I'm generally in a good mood, this is a very personal struggle for me, too.

It is often said by people that even if they get a hundred messages of support or praise, it's the one attack message featuring the false allegation that tends to get their attention. This is a basic human tendency that probably has all kinds of origins and makes all kinds of sense, as problematic as it is.

Even if you're not in a position to receive daily messages of praise from people you've never met, I'm pretty sure you can put yourself in my shoes here. Just imagine, if you will, that every morning when you wake up, like me, you see a few notifications from people commenting on YouTube and other platforms that you're an amazing musician, you should be famous, this song is so great, etc. But then you also get a Google Alert about a minor news story in San Francisco that, among other interests, the guy that just trespassed onto the Pelosi's residence and swung a hammer at Paul Pelosi's head was at some point a big fan of my music. That sticks out, doesn't it? That was my morning two days ago.

Then the next day, yesterday, I got an email from Todd in Eugene, host of the house concert I'll be doing there coming right up. Seating is limited, so as is normal with house concerts, people have to RSVP, and Todd's phone number is on the posters. He got a phone call from a woman telling him in no uncertain terms that I am a Nazi.

The socialists, communists, anarchists, and other folks from ten different countries who praised my music on YouTube yesterday were all very nice, and each comment felt like a kiss on the cheek. But hearing that someone called Todd to tell him that the person he was hosting for a house concert was a Nazi was more like a punch in the stomach.

Sectarianism and division in society -- including bizarre forms of sectarianism within the left, that could result in a left-identified person declaring that a fellow member of the left is a Nazi -- is nothing new, and is obviously not limited to the internet. Neither are phone calls or smear campaigns, which have both been around a very long time now. But the capacity for large number of people to engage in the kind of one-dimensional thinking that could possibly have someone from a left background coming to the conclusion that this guy who by all appearances and according to all of his recordings is obviously a leftwing musician is actually some kind of closet Nazi has never been as worrying a phenomenon as it is today -- certainly not in my lifetime.

Other studies that peppered the airwaves throughout the pandemic have been about how stressful lockdown and all that has been for most people, with general levels of depression, anxiety, addiction, and suicide going through the roof. This is, as far as I understand, the case for people of all walks of life, though it's surely a lot worse for some than for others.

And once again, for society at large as with professional musicians, so many of the factors involved are similar for everyone. None of us were on tour during lockdown, and everyone was to one degree or another spending too much time online, specifically on social media platforms.

But whether it can be empirically demonstrated or not, my hypothesis is that the polarization and conflict that is systematically produced by the basic ways the major platforms are designed -- each with their own built-in system for creating division and conflict, or at least for allowing it to bloom -- is one of the biggest common factors in the general rise in feelings of alienation in society over recent years, and for the flowering of fringe sectarian ideas that would otherwise have a very hard time finding much of a local audience anywhere.

For more specifics on the particular ways different platforms do this work of creating division within society, I can recommend books, documentaries, and also the essay I published last week. To find out how many people there are on the ground in person who think I'm a Nazi, you'll have to come to one of my gigs. I'm doing a west coast tour, playing in Eugene, Santa Cruz, Berkeley, San Francisco, Ashland and Cave Junction between December 7-13, including a protest outside of Twitter HQ on Market Street at 11 am on the 10th.

No comments:

Post a Comment